Bach organ Leipzig

Completed in 2000, for the 250th anniversary of Bach’s death

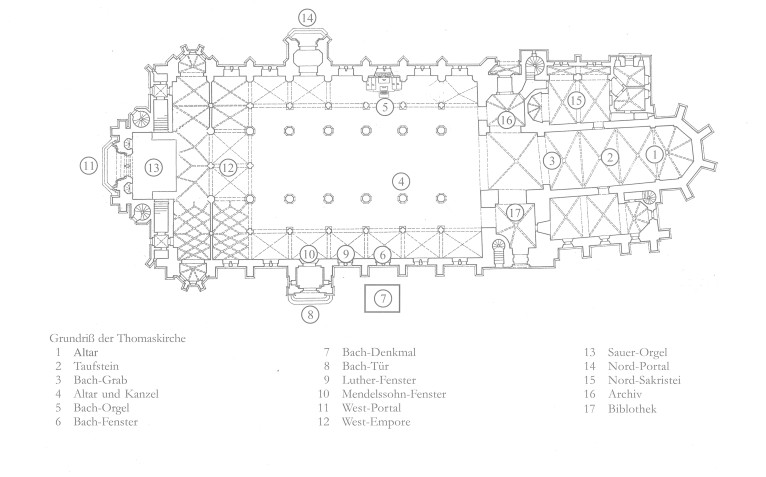

The Thomaskirche is one of the two main churches in the city of Leipzig. The eastern part of the church and the elongated choir were built in the 12th century. The late-gothic hall-church was added between 1482 and 1496. Both have been preserved to this day and adapted to the style of the time. Slender columns divide the space into a central nave, with two side naves of equal height. With its surrounding Renaissance galleries and the all-encompassing net vaulting, the spacious late-gothic hall-church is now a generous preaching and concert church with excellent acoustics. It was here in 1539 that Martin Luther proclaimed the Reformation in Leipzig.

The baroque interior of Bach’s time has for the most part vanished, due to the work carried out between 1885 and 1889. Most of the current furnishing dates from this period. The present interior dates to the 1961-1969 the renovation. The church is partly used transversely as a preaching and concert church, with a second transverse altar and pulpit located in the front part of the nave. The church contains around 1500 seats.

To the west is a large gallery for the Thomaner choir. Here Bach conducted the Thomaner, soloists and orchestra for 27 years. In front of the then uninterrupted west wall stood the great organ. This had been enlarged several times and was also used for continuo accompaniment of the cantatas. On both sides were elevated music galleries for violinists and town pipers. In 1885-1889, the instrument was removed as part of the neo-gothic remodeling of the church. A neo-gothic portal was added with above it space for a romantic organ. This organ by Wilhelm Sauer was originally built with 63 stops distributed over 3 manuals and pedal. In 1908 it was enlarged to 88 stops, following Karl Straube’s recommendations. This instrument, recently restored to its original sound, uniquely represents the sound-conception of Bach’s organ works as perceived at the time: the so-called “Leipzig School”, which is inextricably linked to the names of Karl Straube and Max Reger.

The significance of the church is closely linked to the name of Johann Sebastian Bach and is home to the Thomaner. Since the Bach Renaissance, largely stimulated by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, it has become the most important Bach site in the world, and since 1949 Bach’s final resting place. The church is a weekly draw for listeners from all over the world: not only for the motets and cantatas that have been sung here for generations, but also for the Sunday services with the Thomaner and the Gewandhaus Orchestra.

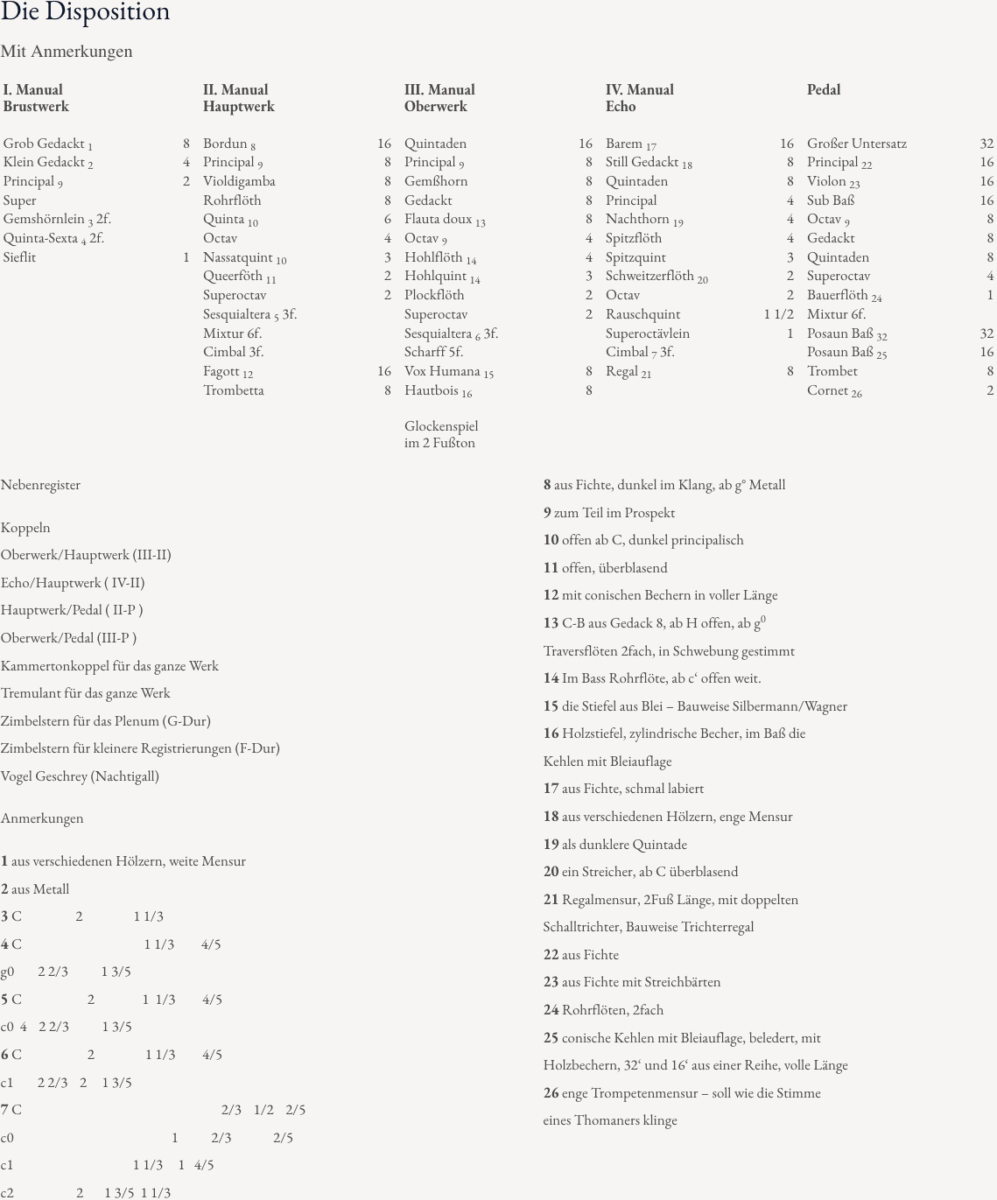

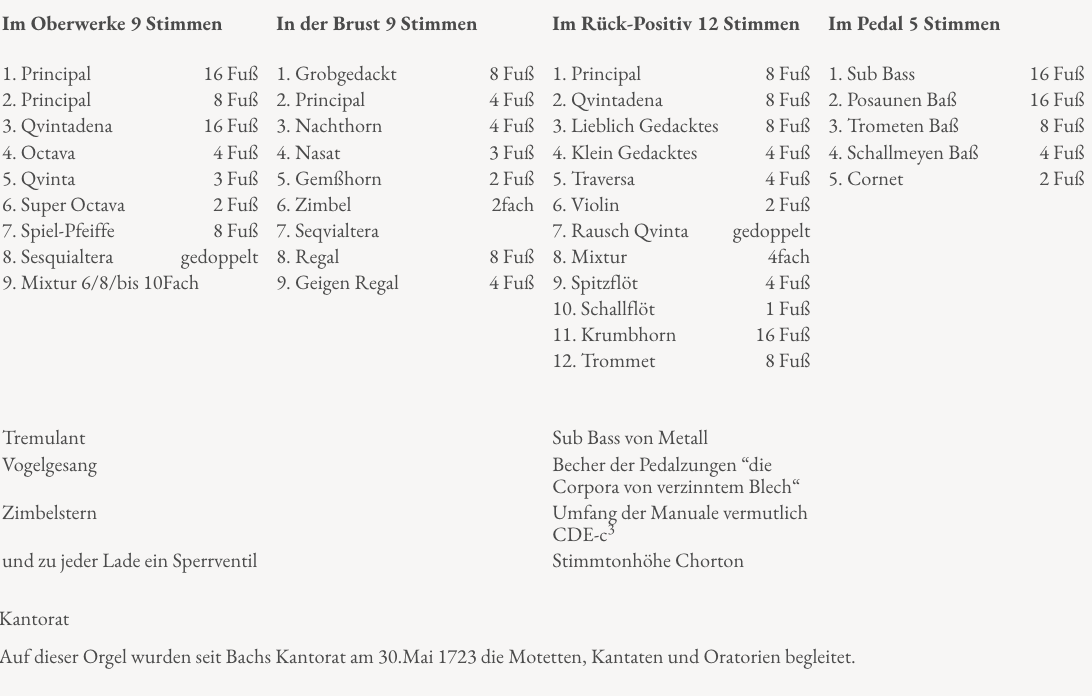

The organs of St. Thomas Church at the time of Johann Sebastian Bach

The "great organ" in the Thomaskirche in Leipzig

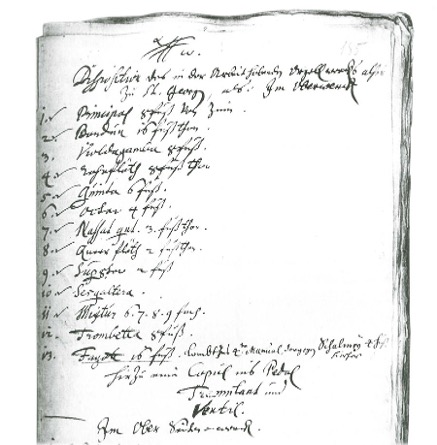

after J.J. Vogel, Leipzigisches Chronicom, Leipzig n.d. (between 1696 and 1714) p. 110 ff

On the pupil’s choir on the evening wall (west gallery) is the large organ…

According to the date on it, this organ was renovated in 1601 and again in 1670 and augmented with new bass stops and chest division. So that today this organ has 35 stops. It has 3 manual Clavier and 1 Pedal and at present 10 bellows.

Specification

The small organ

as a swallow's nest organ on the east wall of the nave

"On which music is struck and played on high feast days"

after J.J. Vogel, Leipzigisches Chronicom, Leipzig n.d. (between 1696 and 1714) p. 110 ff

The Specification

The idea behind the organ project

Ullrich Böhme, the predecessor of the current St. Thomas organist Johannes Lang, drew up three criteria for the new Bach organ in the Thomaskirche:

It It should be an instrument on which the music of Johann Sebastian Bach in particular could be performed.

A similar instrument should have played a part in Johann Sebastian Bach’s life.

The instrument should not be a copy of a still-existing original.today.

A large, dignified Bach organ with a variety of tone colours

In terms of sound, the Bach organ in St. Thomas Church is based on the specification and considerations of Johann Christoph Bach. He was town organist at the Georgenkirche in Eisenach and oversaw the construction of a new organ. During this period Johann Sebastian Bach was born and grew up in Eisenach, where his father was the town piper. He was baptized in the Georgenkirche. Georg Christoph Stertzing was commissioned to build the new instrument, of which the specifications and Johann Christoph Bach’s numerous instructions are preserved. During and after the long construction period, the sound of the instrument was further enhanced and altered. In 1725, Johann Friedrich Wender from Mühlhausen added a 32-foot Posaune to the Pedal division. Johann Sebastian must have been greatly influenced by the construction of this large organ. It probably served him as a model throughout his life.

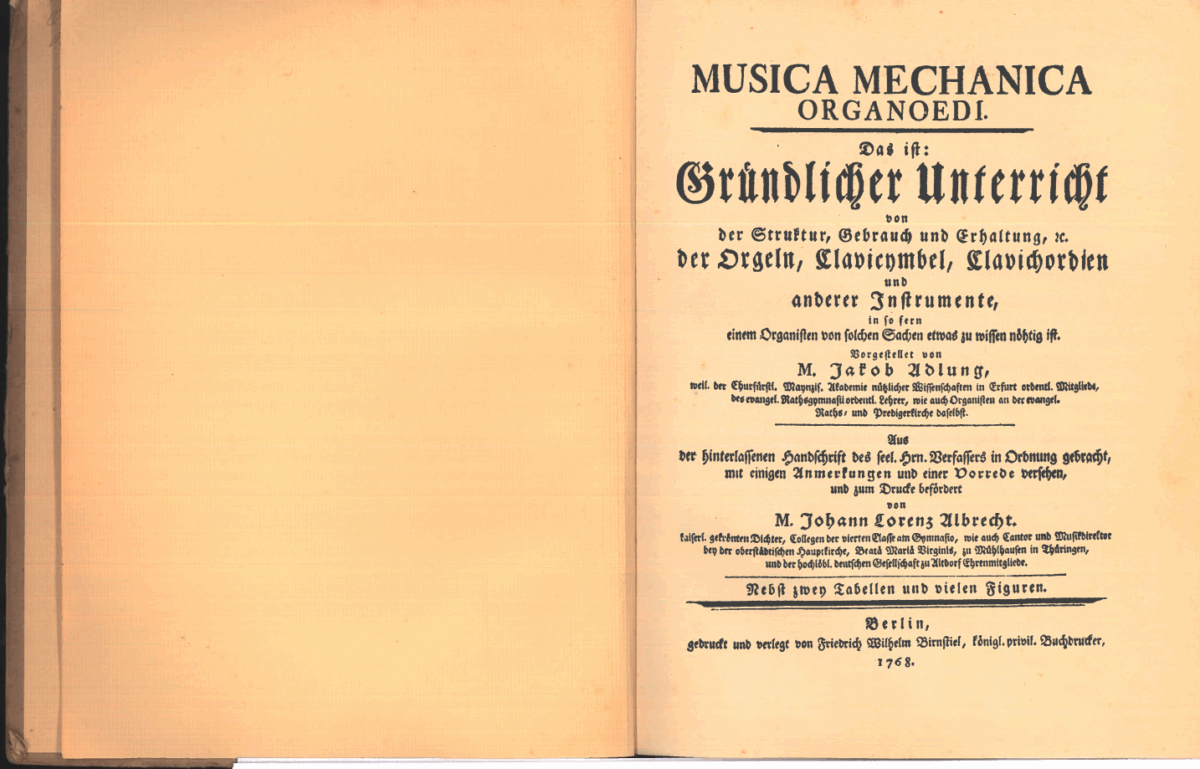

Organ building in Thuringia in the time of J.S.Bach

At the end of the 17th century and in the first half of the 18th century, outstanding artists, musicians, composers and instrument makers worked in Thuringia, with Erfurt at its center. They were influential far beyond its borders in terms of music and instrument making, and had a formative influence on the organ style of Central Germany. The widely dispersed Bach family probably played an influential part by inspiring both organ and instrument making. Organ and instrumental studies were also inspired by the personality of Jakob Adlung, of Erfurt, who taught at the university and was also the organist of the Prediger Kirche. His Musica Mechanica Organoedi are of inestimable value today for the appreciation, not only of tonal construction but also for research into organ building in Thuringia and Central Germany.

The organ builders around J.S. Bach

The following four central German organ builders were essential for the concept of the new Bach organ in the Thomaskirche:

- Georg Christoph Stertzing, whose instrument and tonal concept in the Eisenach Georgenkirche greatly influenced the young Bach.

- Johann Friedrich Wender from Mühlhausen, one of the most important organ builders in Central Germany. He worked with J.S. Bach on several occasions. He built Bach’s Arnstadt instrument in 1703. In 1708/09, he extended and modified the organ of St. Divi Blasii in Mühlhausen according to Bach’s suggestions. Bach was the organist in both churches. Wender and his Mühlhausen workshop were regularly active in neighboring Hesse. Some of his pupils settled there and through their instruments largely determined organ building in eastern, northern and central Hesse.

- Zacharias Hildebrandt, one of the most influential instrument makers during Bach’s time in Leipzig. In 1727/28, he improved the great organ, as well as the Schwalbennest organ opposite the western music gallery. Bach used the instrument for his own compositions. Bach and Gottfried Silbermann jointly prooved the newly rebuilt great organ in the Wenzelskirche in Naumburg. Hildebrandt’s work marks the culmination and conclusion of an epoch.

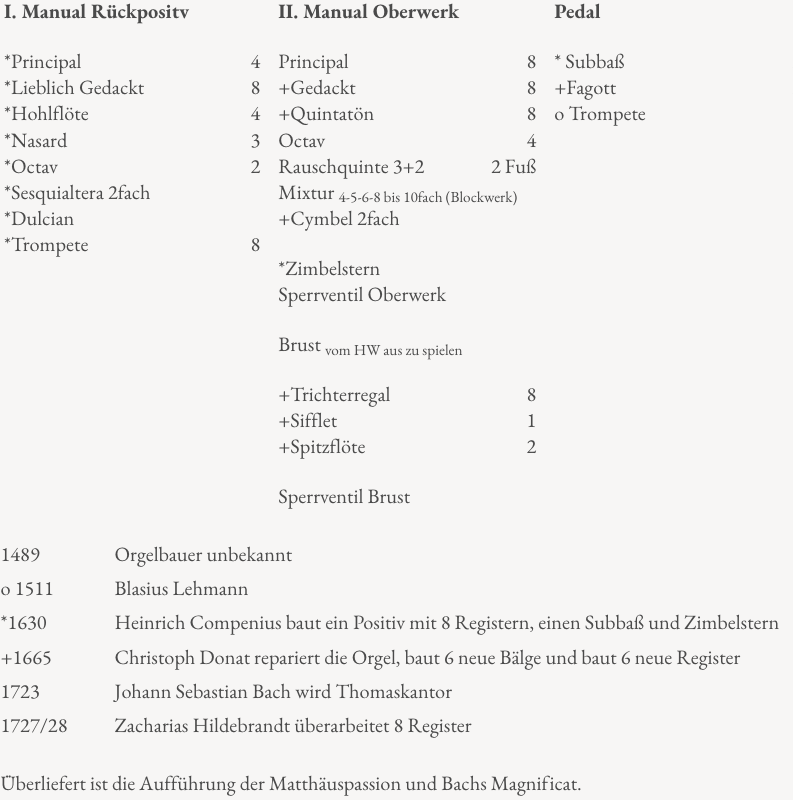

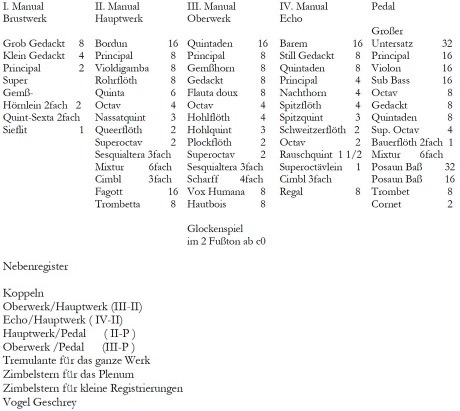

The Specification

The specification of the Bach organ for the Thomaskirche was developed from surviving documentation concerning the former organ of the Georgenkirche in Eisenach and its later modifications. A few stops that had been planned but not built are included in the Leipzig specification.

Reports by the builder Georg Christoph Stertzing during and shortly after completion of the organ were also taken into account for the tonal design of the stop-list. Reports by Johann Andreas Silbermann from Strasbourg and the organ builders Johann Georg and Johann Adam Östreich from Oberbimbach near Fulda were also significant. Silbermann visited the Eisenach organ around 30 years after its completion and wrote down his impressions in detail. The organ builders Östreich produced a detailed report around 100 years after the organ was completed.

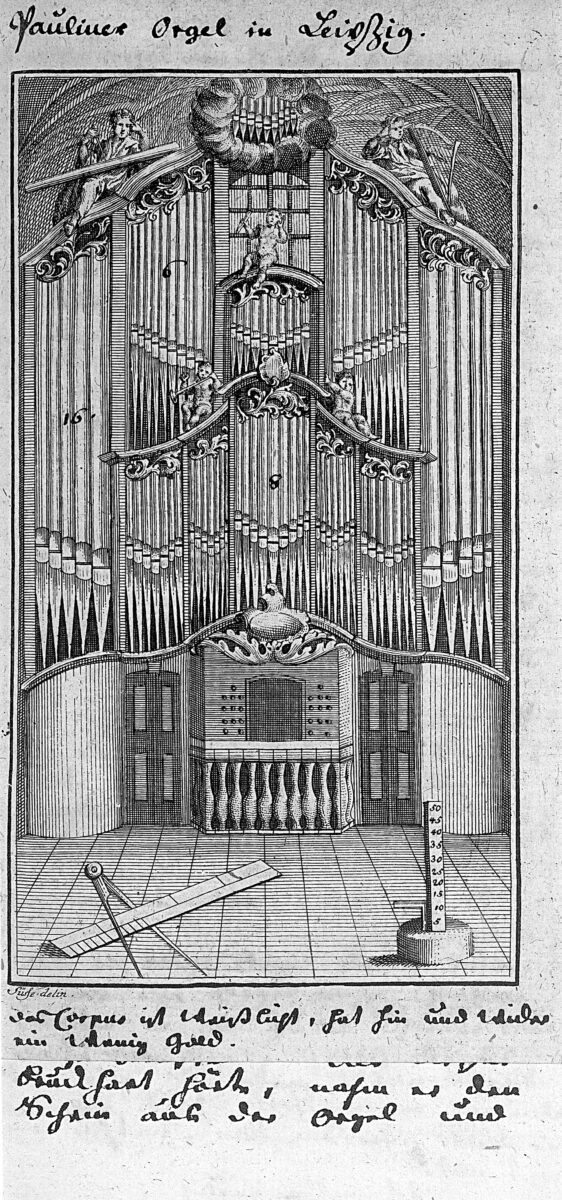

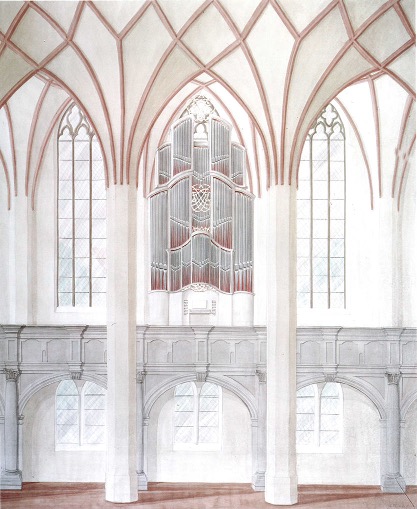

The exterior design

The exterior design of the instrument is based on a surviving copperplate engraving of the baroque façade of the former organ in Leipzig University Church. Bach had proved the instrument during his Köthen period. During his time in Leipzig, it was the instrument on which Bach could be heard: at university events, at general concerts and for the presentation of his own works. It was only logical that this source should influence the exterior design of the new Bach organ.

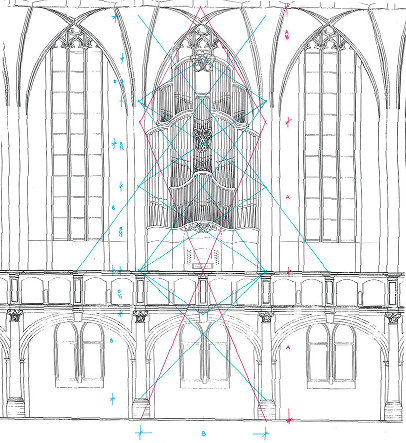

In accordance with the size of the Thomaskirche and the fundamental four-manual specification, an Oberwerk was included in the design. The exterior conception as a whole was aligned on the new location, as well as on the dimensions and proportions of the interior. The form of the baroque-structured case, converging on the center, is intended to make the syntax of the organ and its baroque sound both recognizable and outwardly visible. The details – profiles and curving structure of the case, light-reflecting silvered finials above the pipes, Bach’s emblem as the center of the organ, the upper crowning of case and console, the Zimbelsterne visible from the exterior – all these elements are modern in design. The organ is instantly recognizable as an instrument of our time. Its architectural structure reflects the characteristics of Bach’s music, imbued with inner dynamics, clear proportions and numerical symbolism. It is clearly part of the Thomaner/Kantor tradition, which has always mirrored the present.

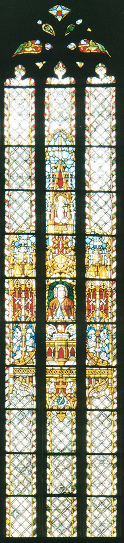

The Bach organ is located on the north gallery in the 6th bay from the west, directly in front of a large window, diagonally opposite the second altar and pulpit. From this position, the sound can reach the entire church. It forms an axis with the Bach memorial-window opposite and the Bach memorial directly outside the Thomaskirche.

The tonal design

Bach had already composed many of his organ works by the time he arrived in Leipzig. His organ style was initially influenced by Thuringia, where the widely-dispersed “Bach family” was located and where Johann Sebastian grew up. He later held organist appointments in Arnstadt, Mühlhausen and Weimar. He was influenced in his early years by his two-year stay in Lüneburg, from where he traveled several times to Hamburg. From Arnstadt, his first position, he undertook a journey of several months to visit Dietrich Buxtehude in Lübeck. In the Hanseatic cities, he would have been particularly impressed by the obligatory use of the pedal. His intensive involvement with organs in general, and in particular with the organ of the Eisenach Georgenkirche, certainly had a lasting influence on his career. The specification of the Eisenach organ, the richly endowed pedal and the variety of timbres provided all the musical prerequisites for his own organ style. Later additions to the organ, such as the addition of a 32-foot Posaune, were also recommended by Bach for smaller organs, for example in Lahm in Itzgrund where, due to his family connections, he acted as an advisor. During his time as organist in Weimar, a Glockenspiel was added to the the Manual of the organ in the Schlosskirche. He regretted that he could not have a “really large and really beautiful organ for his constant use.”

Specification

Pitch and temperament

In Bach’s time, the pitch for organs in central Germany was the Chorton (466 Hz, a semi-tone higher than today’s a 440 Hz). The orchestral instruments for the cantatas played in Kammerton (a 415 Hz, a whole tone lower). For the continuo of his cantatas and oratorios for the great organ, Bach wrote out the parts a whole note lower. The Bach organ in the Thomaskirche is in Chorton and can be played with all stops a whole tone lower by activating the Kammerton coupler.

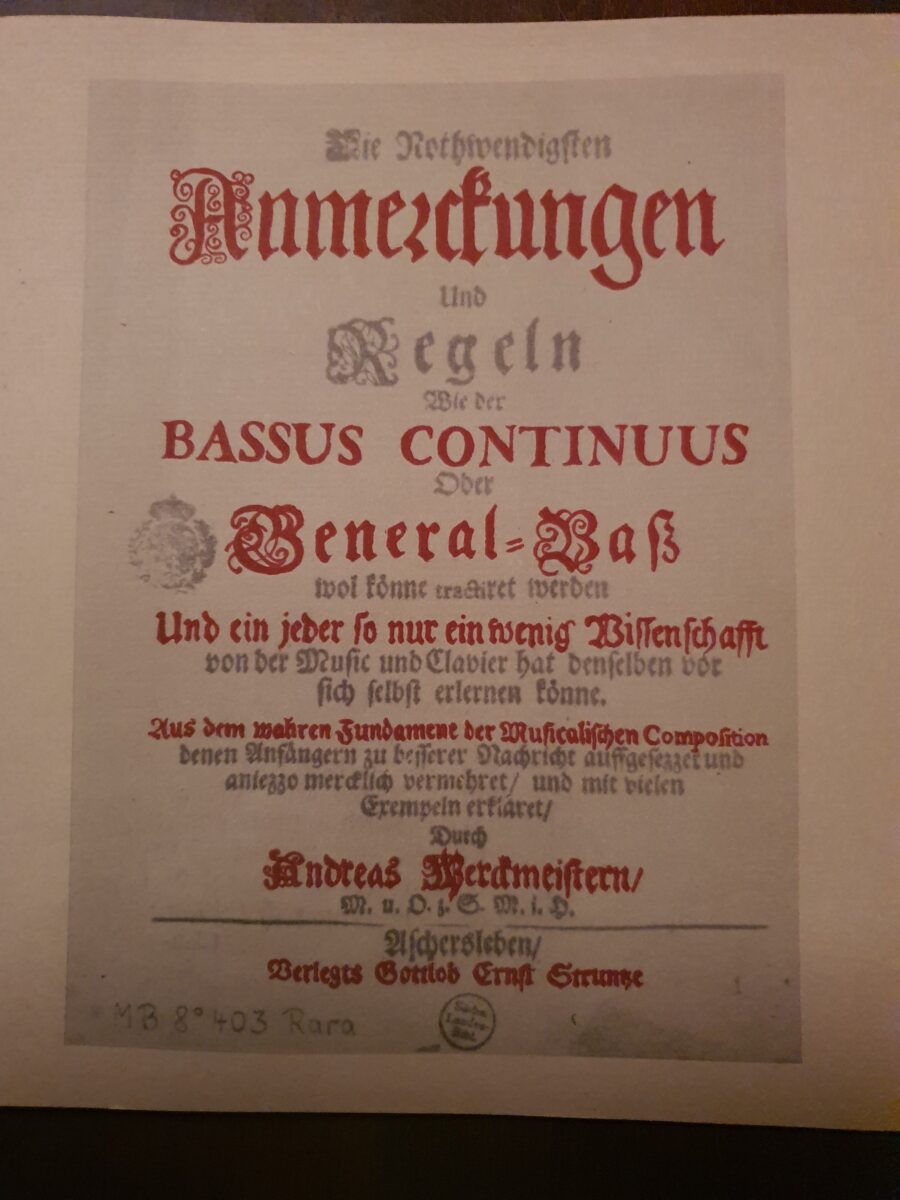

By switching the pitch, a temperament had to be found that was as similar as possible in both pitches. This was essential for the performance of Bach’s late works composed in Leipzig, such as the Dritte Teil der Clavierübung. It was only after the instrument was completed that a document was discovered in the Dresden State Archives entitled “Anmerkungen und Regeln für das Continuo Spiel” by Andreas Werckmeister. This confirmed the tuning system already in use in the Bach organ.

With its musically rich tone colors, the Eisenach stop-list, by Joh.Chr.Bach (1696), is a remarkable discovery. It offers powerful plena, as those to be found in the organs of Gottfried Silbermann in Freiberg and Dresden, and also in the Hildebrandt organ in Naumburg. In the tonal design, the tierce stops are combined into two different Sesquialteras. On the one hand the clear, bright, magnificent plena of the large Saxon organs can be replicated. On the other hand, it is also possible to compose the colorful sound that characterizes Trost’s instruments, partly due to tierce Mixtures. The Bach organ sound, which is both dignified and radiant, is thus particularly perceptible. The organ is in chorton, a semi-tone higher than the current pitch. Both main manuals, HW and OW, are 8-foot with a foundation of Bordun 16 and Quintaden 16 respectively. The Pedal has profound gravity, with two 32-foot stops, Untersatz and Posaunbass, and four 16-foot stops of varying tonal contours. The overwhelming grandeur of Bach’s works are enormously enhanced by the wide tonal range, from low basses up to the multiple ranks of Mixtures and Cymbals. The essence of the wide-ranging specification lies in the variety of individual timbres, representing primary emotions: astringency and sweetness, a capacity for grandeur and also for elemental sorrow, pain and longing, as opposed to joy and jubilation. These are timbres that reflect suffering, death and resurrection which are at the center of all Christian thought and action, and exemplified in Bach’s cantatas, passions and oratorios. The instrument is essentially an exceptional cantata orchestra, capable of reproducing the emotions of Bach’s music. More especially, a sensual rendition of Bach’s organ works requires a large variety of individual timbres, a sensitive action and reactive organ-wind. Only through the interplay of these three specifics can Bach’s organ music find its ultimate expression: an intimate dialogue between soul and spirit.

Résumé

Joh. Christoph Bach’s ingenious specification for a large and stately instrument was the original inspiration for the Thomaskirche Bach organ. In order to fulfill its particular task, the new instrument was not assigned to one specific type of organ: it was planned to reproduce the universality of Bach’s music in its whole range of harmonious expression and tonal diversity.

The instrument’s pitch is a semi-ton higher, in Chorton. Bach’s organ works can thus be experienced in a particular way with luminous sound and grandeur. Depending on requirements, the Bach organ with its four manuals and pedal, and its full range of stops, including the two 32-foot stops, can also be played a semi-tone lower in Kammerton . This creates unique possibilities for music in the Thomaskirche, especially for Bach’s cantatas.

Technical data

The organ case

is outwardly baroque in form, but modern in details. All components are made of mountain spruce, the surfaces are shaped and finished with plane and scraper and then painted, using historical techniques. Transitions from pipes to case frames are silvered and lustrated.

The structure of the instrument

is a reference to the surviving case of the former organ in the Pauliner Kirche in Leipzig, also known as the Universitätskirche. The baroque layout corresponds to the exterior of the instrument. Above the console, on both sides of the keyboards, is the Brustwerk with Principal 2 in the façade. Behind it, slightly lower in the middle, is the Unterwerk, sounding as an echo. To the right and left is the Klein-Pedal, with Principal 8 in the façade. Above in the centre is the Hauptwerk, with Principal 8 in the façade. Above the Hauptwerk is the Oberwerk, with Principal 8 from F in the façade. On both sides, in the rearmost part of the lower case, is the Grosspedal. In the window niche are the Posaune 32 and 16 feet stops. The pipes of the Untersatz 32 are housed in the gallery staging, with sound exits between the levels.

The Console

is centered beneath the Brustwerk and has four manuals:

I. Brustwerk

II. Hauptwerk

III. Oberwerk

IV. Echo

The compass

of the manuals in Chorton C-f3; in Kammerton C without C sharp to f3,

in the pedal in Chorton C-f1, in the Kammerton C without C sharp to f1. C sharp plays c sharp0

The couplers

are built as mechanical action couplers.

The Kammerton coupler

The instrument is tuned to Chorton, a 466 Hertz. By using the Kammerton coupler it can be converted to Kammerton, a 415 Hertz. A lever in the console converts the entire instrument.

The key action

is mechanical, suspended action with a very direct touch.

The stop action

is mechanical, with drawstops to the right and left of the keyboards.

The wind system

is located under the gallery levels, to the right and left of the instrument. To the right are two wedge bellows, primary and blower for the manuals. To the left two wedge bellows, primary and blower for the pedal.

The plenum wind

can be connected by means of an additional wedge bellows behind the Oberwerk.

The pipework

in metal consists of different lead/tin alloys from 5% to 83% tin content. The metal is cast conically to thickness and reworked with scraper. The languids are cast in lead.

The reed stops have shallots and reeds made of brass, constructed according to historical methods.

The Glockenspiel

is made of bowl-shaped bells with their own repetition mechanism. They can also be played in Kammerton by using the Kammerton coupler.

The pitch

is 466 hertz in normal use, but can be switched to 415 hertz using the Kammerton coupler.

The temperament

is specially conceived for Bach’s music, both at 465 and 415 hertz.

The tuning of the organ -

all pipes are cut to length.

The voicing

was carried out in the church and took about 8 months.

The temperament of the Bach organ from the organist's perspective

Johannes Lang

The question of the correct temperament for an organ has been a central issue in organ building for centuries. While this issue was a regular topic until the 19th century, it was then practically considered to be a thing of the past, due to the widespread use of more or less equal temperament. It flared up again with the return to historical organ building praxis.

There is a rich tradition of well-tempered tuning instructions for baroque organ building in Central Germany from researchers such as Neidhardt and Schröter, so that we can assume that these systems were in use in Central Germany, at the latest with the evidence of Neidhardt’s temperament on the Wenzel organ in Naumburg.

For the question of tempering the Bach organ, it was therefore obvious that these systems could be used as a guide, even if for various reasons the present temperament is a new creation.

The quality of the thirds ranges between 6 cents (C major) and 22 cents (C sharp major), rising quite evenly depending on the number of accidentals. The quality of the fifths ranges between 0 and -4 cents, whereby the fifth in F major is of the best quality at -2 cents in the central keys.

In my opinion, this well-tempered tuning offers the perfect mixture of clear key characteristics with still clearly perceptible semitone steps of different sizes, but gentle transitions in the change of characteristics and the possibility of being able to play well in all keys. I perceive the temperament as pastel in quality. It seems to me to be ideal for Bach’s music and appears more “well-tempered” than Bach-Kellner, for example.

In St. Thomas Church, the temperament of the Bach organ has to fulfill a dual role: it has to function at two different pitches (465 and 415 Hz). To use the organ at 415, the center of the temperament shifts to D major with the best third. The key characteristics thus shift in such a way that the quality of the sharp keys is still very good even in keys with many accidentals (B major corresponds to the A major quality in 465!), while the B flat keys become rapidly tense (B flat major corresponds to the A flat major quality in 465).

For baroque ensembles playing in Kammerton pitch of 415 Hz, this characteristic is somewhat unfamiliar at first and pieces in flat keys in particular need some time to find their intonation due to the rather low Bb and E flat.

However, we can assume that this corresponds to the reality of Bach’s time, in which an organ transposing downwards in the tuning pitch of 465 Hz accompanied a choir and orchestra in 415 Hz. For example, in Bach’s most festive works, most of which are in D major, the organist had to play in C major. The arias with the darkest character in the Passions are mostly in the key of B flat, which leads to a corresponding sound in the organ.

This should lead to the realization that when tuning chest-organs to accompany Bach’s vocal works, a temperament centered on D major is always chosen.

It is a pity that the temperament of the organs in St. Thomas Church at the time of Bach has not been recorded. However, as we encounter such a wide range of keys in Bach’s work, including organ accompaniment, it must have been a temperament that allowed for satisfactory playing in all keys.

Finally, it must be remembered that temperaments were always set by ear and that there must have been a great wealth of regional variations.

In any case, I can report from experience that it is a delight to accompany baroque ensembles with a temperament centered on D major and, especially in the Passions, to trace the characteristics of the keys in a completely different way than is the case with the temperaments in use today, which are all centered on C major.

The tuning can be accessed at: https://bund-deutscher-orgelbaumeister.de/stimmungen/

It is listed under this link in group 5.